Last week, I came across this story put out by Harper Magazine by a reporter (Ted Conover) who was tasked with becoming a USDA inspector for the meat processing company, Cargill in small town rural Nebraska. Upon reading it, I came out with mixed feelings. My first feelings were that overall, it wasn’t what I thought it was going to be. I assumed it would be that classic “bashing large agribusiness” or “uncovering the horrors of the modern slaughterhouse” but instead Conover re-enforces the necessity USDA meat inspectors play to our meat system today.

Just as Cargill, I am however, disheartened to see that Conover didn’t disclose his intentions to Cargill before applying for the position. Cargill opened their doors to Oprah last year and has since put up a visual tour of their operation in Dodge City, Kansas, Cargill has been working more and more towards transparency in their business practices. By working together, I believe, this story could have not only been a little more factual, but it could have also been more widely distributed and used as a tool to connect costumers with how their food is produced.

Conover had zero background in animal science or any sort of prior training in meat inspection before taking on this job. His career has been as a journalist. And this story shows you that. There are a few issues with the story when it comes to facts versus perceptions. But for someone without knowledge of the industry, you simply wouldn’t know these things. So I’d like to shed some light on some of the inconsistencies/errors I find in the story if you read through it in full text.

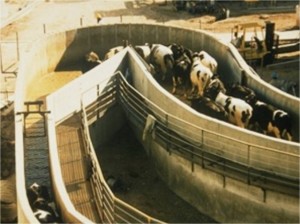

1. “They’re (the cattle) are scared. They don’t want to die” —

In the article, this statement was said to Conover from another employee. So it was taken as a quote versus fact. But the fact is that modern slaughterhouses and especially large scale facilities like Cargill work hand in hand with people like Temple Grandin who have revolutionized the handling of animals. Facilities have been remodeled in order to incorporate these new handling systems suggested by Grandin which consists of non-slip floors, serpentine curves directing the cattle where to go, dimly lit rooms so that the cattle move towards the light. And if you go to a facility like Cargill, you will see that these systems are working and that cattle aren’t displaying signs of fear. One of the first things you’ve got to realize when handling herd animals like cattle is that they like to travel in numbers. When cattle are separated, they stress out and begin to show signs of fear. That is one of the reasons when you often look at holding pens or even feedlots it seems like the cattle may be shoved together in a small space, but the reality is, they don’t like to be alone. Being in close contact with one another is how they feel comforted. Signs of fear in cattle are typically vocalization (lots of moo-ing or bellowing), eyes wide open with head high, panting, lots of defecating. In the end, stress on cattle leads to poor meat quality so if any slaughterhouse is looking to maintain a high standard of quality product, they will do their best to make sure cattle stay calm and show no signs of fear.

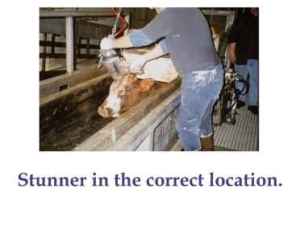

2. “If one shot doesn’t do the trick, the knocker does it again.” —

When a slaughterhouse uses a captive bolt method of rendering insensibility in animals, it is called “knocking” in the industry. The person using the actual captive bolt is called a “knocker” and the actual action of the captive bolt rendering the animal unconscious is called a “knock”. The knock renders the animal completely insensible. The animal feels no pain and is no longer conscious. According to Grandin, “plants that have an effective systematic approach to good captive bolt stunning practices will usually average about 96 to 98% of the animals rendered insensible with a single shot. Some plants will routinely shoot animals twice to insure that they remain insensible.” So although it is not uncommon for plants to “knock” an animal twice, it is not done because the first one was not effective. The handling of animals humanely doesn’t just fall on the shoulders of the individual plant, there are USDA (or FSIS) directives on humane slaughter that talk about multiple knocks to render an animal unconscious being unacceptable. When a USDA inspector witnesses what he/she believes to be inhumane handling or slaughter, they are required to report it. There are varying degrees of this, but in some cases, it can cause the inspector to shut down production or even shut down the plant until a review is done to ensure handling and slaughter are humane.

3. Carolina (a fellow meat inspector) says “they aren’t really dead” and talks about the heart beating the blood out —

Once the animal is knocked, it is brain dead (insensible). There is no more brain activity and this can be ensured by a few signs: no vocals, no eye movement, the head is limp and floppy, often times the tongue is out, and no rhythmic breathing. After the animal is knocked, one leg is shackled and is hoisted up in the air. It is at this time that it is common to see the animals leg flexing, kicking, twitching, thrashing, or whatever you want to call it. Animal rights videos especially like to show this as a sign the animal is still alive and that is not true. It is important to look at the head, it should be limp and floppy, hanging straight down. An animal that has not been rendered fully insensible will attempt to lift its head up or curl it’s tongue, their will also be eye movement (blinking). Shortly after the cattle are rendered insensible, one leg is shackled, and they are hoisted, they will be what we call “stuck” which is essentially where their throat will be cut to let out the blood. If animals are thought to be rendered insensible in an inhumane way, the entire carcass could be condemned and unable to go into our food supply. The whole carcass will basically be unusable. During the knocking process, there is an inspector present that will ensure the knocking is being done right as well as animals are being rendered insensible. Having an animal that is potentially still conscious on the rail poses not only a risk for the animal but also an extreme risk for the employees who are coming in very close contact with the carcass. There is no reason why a slaughterhouse would not want take the proper steps to ensure they render an animal completely insensible 100% of the time if they can.

4. Antibiotics Cause Abscesses —

Antibiotics in livestock use are used to prevent abscesses, not cause them. For a great post about antibiotics and WHY they are used in animal livestock, check out Mommy at the Meat Counter. A few phrases from her blog address the issue of antibiotic residue in meat: “The Food and Drug Administration regulates the approval and use of antibiotics in animal medicine. Any antibiotic that is given to a food animal has a specified ‘withdrawal time’ which is the amount of time that the antibiotic has to be withdrawn from the animal before it is slaughtered. These times are based on how long it takes the animal to process the antibiotic so that it is eliminated from the body. Farmers must wait to slaughter an animal for that amount of time after giving the antibiotic to the animal or they will be breaking the law.” The FSIS or USDA inspectors also test for antibiotic residue in meat and have a good monitor on this sort of thing, as Conover actually discusses in his article. His facts, however, about antibiotics and their use in livestock are a little skewed.

Conover also brings up the issue of liver flukes and liver flukes are a common parasite in cattle, even in some of the cattle that we butcher. Besides a yuck factor, there really isn’t anything wrong with finding a liver fluke as they pose no threat to food safety as long as they are removed and the tissue is cut out. Liver flukes can, however, be prevented by giving your cattle a dewormer leaving enough withdrawal time prior to slaughter. For more information on preventing liver flukes, visit this site.

5. “To date, companies have blocked proposals to let USDA set standards to regulate pathogens in meat” —

This is 100% false. USDA does indeed have systems in place to regulate pathogens. With beef, USDA has mandatory testing for E-coli 0157:h7 as well as voluntary testing on many other strains of E.Coli. It is a serious criminal offense in the meat industry to knowingly send out meat that has tested positive for E-coli 0157:h7. As much as the meat industry would love to rid our food system of things like E.Coli or Salmonella, there is no possible way to completely eliminate it. Just as farmers can’t do anything to eliminate the risk in their cattle meaning grass-fed, grain fed, whatever kind of feed. None of it completely eliminates potential risk for pathogens in meat. As processors, we can use the best testing to monitor it, we can use the best sanitation practices to try and control it, we can minimize risks to the best of our abilities, but as Amy from from John’s Custom Meats shares with us in her blog post, we can’t eliminate it. Amy does a great post describing what it takes their small butcher shop in KY to test for E.Coli 0157:h7, you can check it out here. Regardless of how well we do our jobs, it is still up to all of our customers to ensure they use safe handling instructions when handling raw meat. Make sure to keep raw meat products refrigerated or frozen, keep raw meat and poultry separate from other foods, washing all your working surfaces utensils and hands after touching raw meat or poultry, make sure you cook to the proper temperatures, and keep hot foods hot and refrigerate leftovers.

6. ” It seems smart to avoid ground beef. Most E.Coli contamination comes out of grinding plants, where the provenance of the meat can be practically anywhere in the hemisphere and the standards are often lower. Grinding conceals almost all sins.” —

Grinding establishments, especially after the “uncovering” of lean finely textured beef, are under heavy regulation and scrutiny. Grinding operations have a multitude of testing requirements for the plant itself and have considerably more testing done more often than say the slaughterhouse portion of the plant. Plants use what is called a HACCP plan (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) to document all of this information and more. This is done in large and small plants alike, federal or state. The steps taken to ensure food safety aren’t easily simplified. There are many and multiple steps as well as a lot of paperwork required to ensure that you are providing your customers with the safest products you possibly can. If the particular grinding plant has to receive meat from somewhere else, they have to provide proof that the plant they are receiving the meat from has indeed took steps to reduce risk for pathogens in steps which we call “interventions”. This is done by a Certificate of Analysis or if you are the one grinding your own beef, you are required to have documentation to prove that you are taking steps to reduce risk for pathogens. This can be done by carcass testing for pathogens such as E.Coli. Essentially, the HACCP plan is in place from the start and continues to the finished product. It works to identify, control, and prevent any hazard to food safety through a serious of “interventions”. So in reality, grinding covers no sins but instead exposes them all! For more information about how hamburger is made and the safety of it, check out this great article from Beef 101.

Grinding establishments, especially after the “uncovering” of lean finely textured beef, are under heavy regulation and scrutiny. Grinding operations have a multitude of testing requirements for the plant itself and have considerably more testing done more often than say the slaughterhouse portion of the plant. Plants use what is called a HACCP plan (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) to document all of this information and more. This is done in large and small plants alike, federal or state. The steps taken to ensure food safety aren’t easily simplified. There are many and multiple steps as well as a lot of paperwork required to ensure that you are providing your customers with the safest products you possibly can. If the particular grinding plant has to receive meat from somewhere else, they have to provide proof that the plant they are receiving the meat from has indeed took steps to reduce risk for pathogens in steps which we call “interventions”. This is done by a Certificate of Analysis or if you are the one grinding your own beef, you are required to have documentation to prove that you are taking steps to reduce risk for pathogens. This can be done by carcass testing for pathogens such as E.Coli. Essentially, the HACCP plan is in place from the start and continues to the finished product. It works to identify, control, and prevent any hazard to food safety through a serious of “interventions”. So in reality, grinding covers no sins but instead exposes them all! For more information about how hamburger is made and the safety of it, check out this great article from Beef 101.

I hope this brings to light some myths and addresses some common misinformation that is spread around about the meat industry. And if you get a chance, check out the Harper’s magazine and Ted Conover’s article. It is very interesting to get the perspective on someone who had never been in a slaughterhouse before. He validates the fact that meat inspectors are necessary, but they also work a strenuous job and should be recognized for that. Did you read the story…? What were your thoughts..?

Article Full Text: HarpersMagazine-2013-05-0084386

Related articles

- Ted Conover Goes Undercover as a USDA Meat Inspector (harpers.org)

- Writer goes undercover as USDA inspector at Schuyler beef plant (journalstar.com)

- Cargill calls Harper’s piece a ‘fable-like tale’ (journalstar.com)

Pingback: Pork Chops Are No Longer Pork Chops | Chico Locker & Sausage Co. Inc.